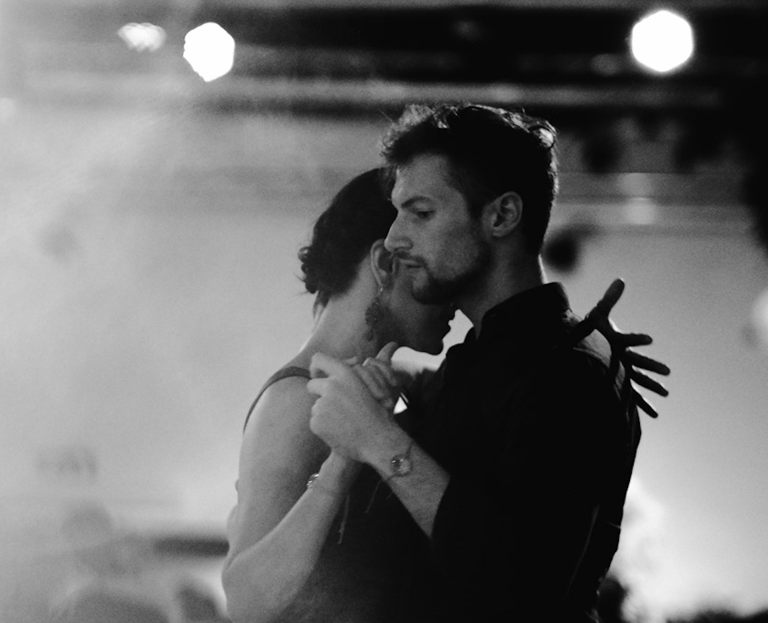

What tango dancers and babies have in common?

Today is a little anniversary - my tenth year of dancing tango.

There’s a tango joke: the first ten years are the hardest. That feels true to me.

At the same time, some people dance for years without much improvement or joy, while others learn quickly and begin teaching early. There’s something essential that helps us improve—or at least fail better.

When I reflect on any dramatic improvements that I made (in tango and life), it wasn't so much from practicing the same patterns over and over. The 10,000-hour rule—that you need to repeat something for 10,000 hours to master it—feels overrated to me. Obsession with perfection, technique, monthly private classes, and more events—none of that really helped how I felt. It didn’t improve my enjoyment or even my dancing level.

Despite occasional sparks of amazing dances, I wasn’t happy. I couldn’t feel content with my experience. I looked outside for better partners, chased a better level, and better marathons. What helped was working on myself - therapy, learning about my body patterns, doing free somatic movement, accepting that people are how they are, and I'm the one who is responsible for my feelings and experiences. It did include dance and practice, but it wasn’t about repeating the same moves or the same attitudes.

Last month, I co-facilitated three online somatic tango workshops with another embodiment specialist and tango teacher. One woman’s feedback really summed it up.

She said,

“I had a secret request to regain interest in tango. To get back its magic, its breath, its charm, which I had lost over time in my body.

To be honest, I had already despaired of getting it back, I just resigned myself to the fact that – so I go on, to other things.

But after today's workshop! I know exactly what to do if I suddenly lose it again. I know for sure that all this magic is only in my body, that everything depends only on me, that I don't need a super-partner, or a super-atmosphere, or something special outside of me.”

What’s the magic pill?

Well, we practiced yielding. Relaxing into our own body, trusting the ground, the weight of gravity, softening into the touch of the partner. And then we practiced pushing from that, then reaching into space, grabbing, pulling, and yielding again. In somatics, they call it the Cycle of Satisfaction.