Add your promotional text...

From Greeks to Strange Squiggles

My Story of Starting, Losing, and Rediscovering Art

5/4/20258 min read

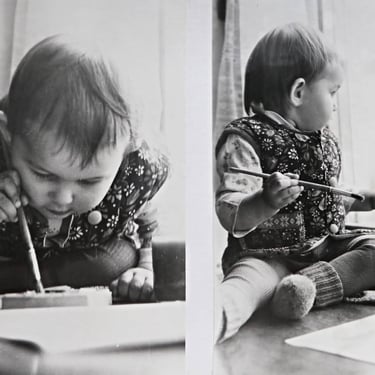

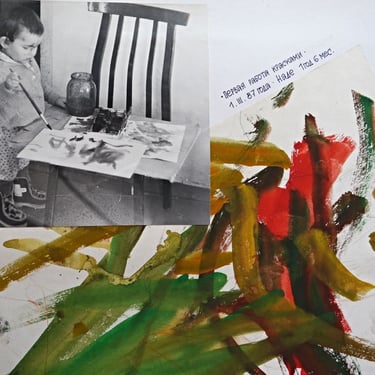

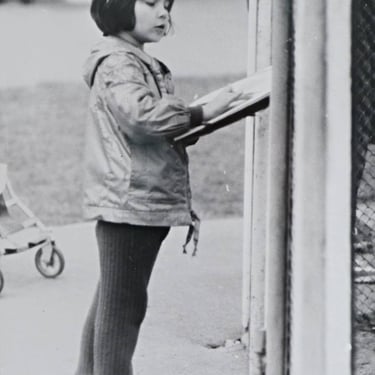

I was born into a family of artists… It sounds quite romantic until I add — in a small provincial town in Russia on the border with Ukraine. Most of my first childhood pictures are with a paintbrush, so I was probably learning to paint at the same time as crawling and speaking.

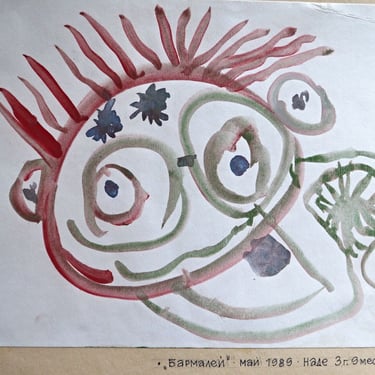

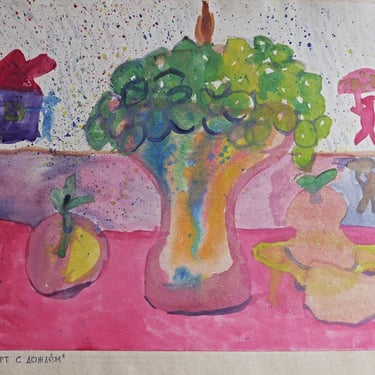

According to my mother’s notes on these ‘works of art’, I created my first abstract piece at the age of 1.5 years.

Ironically, my first memory of painting something comes with the first experience of being told to correct and change it.

I attended an art school for children from the age of nine to fourteen, where my mother was teaching. The program was quite a strict academic one, in the best traditions of the Soviet school, meant to prepare you for entering an Art Academy.

So, apart from the many hours of technique, composition, and painting, we studied art history and critique, applied arts, and sculpture, went out to paint en plein air in summer, and completed the mandatory yearly exhibitions. Those were hung in a big hall full of naked Greek and Roman statues, which provoked hysterical laughs among our school classmates who came for scheduled visits. (Nothing like a tiny penis of Hermes or Aphrodite's boobs to distract the kids from absorbing culture.)

The art school was both a torture (long hours three times a week after a normal morning school shift, often being so hungry by the end of the day that we ate parts of stilllife, getting used to the corrections and criticism early on) and a heaven for experiencing a different reality full of beauty, history, and aesthetic that wasn’t so available to teens in a small town in post-Soviet times. There wasn’t much beauty around, let alone subtlety or sophistication. My mother used to forcefully drag me to all the exhibitions saying, ‘You’ll thank me later’ (which I could do thirty years later, although I’m no longer sure which part I’m grateful for).

The academic-style training both gave me a lot of technical skills and a feeling for colour and composition, and dried up any desire to create something from my own ideas. In fact, having your own ideas was not highly encouraged. After graduation, I promised myself not to touch a pencil again.

At fifteen, I won an English-language scholarship to go to the USA for a year of school exchange. The trip itself was life-changing in many good and horrible ways, but one thing that definitely shocked me was the art classes.

In the very first session, I discovered that I could draw better than the teacher but didn’t have any ideas other than to copy objects. I was told that I’m not very creative and can’t take any of my drawings further than just a representation of reality. On the other hand, my classmates were painting abstract red chairs on yellow backgrounds, messing with mark-making and comics… One of the weirdest guys in the class drew a snake that drowned in the toilet. I was told by the teacher that if we were to combine my technique and his originality, that would make interesting art.

Needless to say, my view of the art world kind of shattered that year. I still didn’t understand anything and just resorted to calling all of that ‘bad art’, but a seed of doubt was planted. What if my teacher, even my parents, were not so right? What if it was only their taste? How come there were other huge countries where art could be so different?

Another important thing that came into my life that year was dancing — and it came to stay.

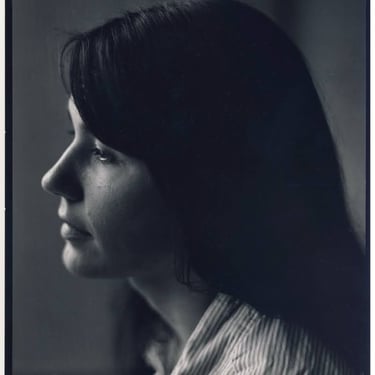

I don’t remember a particularly disappointing or traumatic moment — art just gradually faded out of my life as a distant childhood memory. University with language studies, teaching dance and performing, and getting more interested in psychology, dance, and photography. I started to dream about a dance career, or at least studying movement therapy, as well as finally leaving Russia and moving abroad for more opportunities.

The next twelve-year period was dedicated to bellydance, tribal fusion, going to contact improvisation classes and jams in Moscow, organising festivals and shows. So, in a way, art transformed into my stage performances and costume-making. The body was my joy, and art seemed just an outdated and slow medium.

Then I moved to Ireland, with all its strange contemporary art and dance that I couldn’t place anywhere on my map of what’s beautiful or good. Instead, I studied media, design, and writing. I continued to dance, trying physical theatre, acting, and photography. I worked in a studio shooting actors and dancers, volunteered at dance festivals, and found a Stanislavski method school and corporeal mime, and even produced a small dance theatre piece.

It was a very creative period of trying out so many pathways and changing my views, but also laced with insecurity and inner criticism. The shadow of the ‘real art’ I inherited caused me a lot of suffering, albeit propelling me to strive more. At some point, I lost the fight with it — maybe it was too early, or I was lacking the inner support — but I gave up on the idea of a creative career.

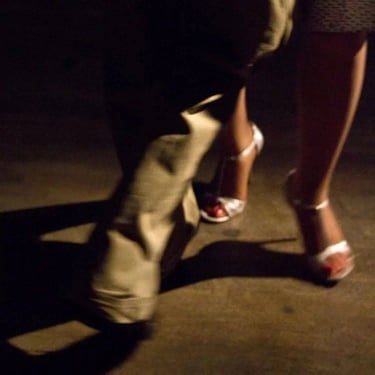

Reaching my thirties, and after a breakup, I took up Argentine tango and started working in the tech industry with linguistics. Art transformed itself into late-night classes and milongas, now learning to dance with someone after years of soloing. I understood more about people’s psychology through touching them, and I wanted more and more to go ‘inwards’ to the dance that was happening unseen in the spaces of relating.

How did I change because of the person who embraced me?

How had they changed because of my embrace?

Or maybe we both changed for some other alchemical reason?

Making an involuntary career in tech didn’t leave much time for art. Life, tango, and relationships brought up my shadow again and again, so I moved into studying Reiki and Jungian psychoanalysis, and went back to contact improvisation.

The writing continued, photography was easy enough to keep as a hobby. I traveled for tango and CI events, now focused on the art of touching.

Touch that moved the energy in the body, that created a memorable twelve-minute experience on the dance floor, touch that could heal and go deeper into the human soul. I wanted to find meaning, not only movement or beauty.

It probably would’ve ended here if COVID didn’t happen. It was a difficult but transformational time for many; for me, it was the point of finally deciding to leave the job, take a risk, and accept a scholarship to study Body-Mind Centering in Spain.

Since the world was ending anyway, I might as well try, right?

By then, I had tried various therapeutic and embodiment methods through contact improvisation festivals. The idea that I could touch through the body and into the tissues, organs, fluids, observe the person change, and feel the interconnectedness of all things, intrigued me immensely. The promise of finally combining everything I loved — dance, touch, psychology, relating, and therapy — to finally make sense and make meaning, was too good.

The reality, of course, was a little more than what I asked for.

Although wonderful and deep, the method was also vague, lacking structure, and sometimes, the actual method. Experiential anatomy meant all experiences were valid, highly subjective, and often very metaphorical. I wasn’t a trained dancer, so the intense hours of moving were hard on my body. Sharing space with others (who didn’t speak the same language or understand my mentality), lack of support, exhausting mental and emotional states of somatic explorations that brought up trauma — I wasn’t prepared for the ‘gifts’ of my dream coming true.

Each profound experience of diving for body wisdom left me wrecked and recovering for weeks after each module. I started therapy again and seriously considered quitting halfway through the three-year program period.

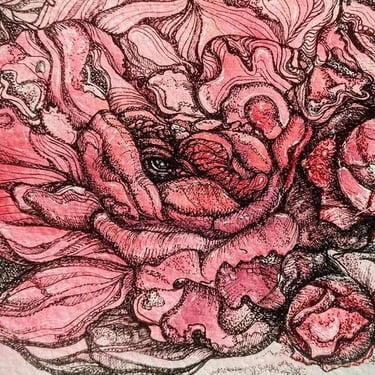

At the same time, Spain surprised me by bringing a sudden desire to try art again. I started dreaming of painting, illustrating my writing. I dug up my old sketchbook, with unfinished, sporadic works. I found artists on Instagram and listened to podcasts daily about the life, work, and daily business of artists who had lives so wonderfully different from my parents or their art circles, that it seemed an alternative reality. I was touching the paper very occasionally, but inside, I was preparing to slowly dissolve the ‘corporate’ identity.

I was even lucky to find a teacher who was trained in the very classical academic style in Madrid and Florence. Going to her classes was like stepping into a living memory of my adolescence — the smell of paint, the wooden easels, the nude studies on the walls. My hands remembered how to sharpen the pencils with a knife to a long pointed graphite end, how to touch the paper in various ways and produce textures… It was fascinating to study again, to work for hours, forgetting about the cold in the studio and not feeling my body.

But this is where the body, now much better connected to my ever-escaping and wandering brain, started to win. I wanted to make art that said more about me than about my hand skills, that came from the body-soul space, the soma, not the external ideals of the Romans and Italians.

On a random Facebook post, I saw an invitation to a BMC & Art class run by Marina Tsartsara — it seemed made for me. What followed that online class was meeting an inspiring teacher, a future mentor, and a friend.

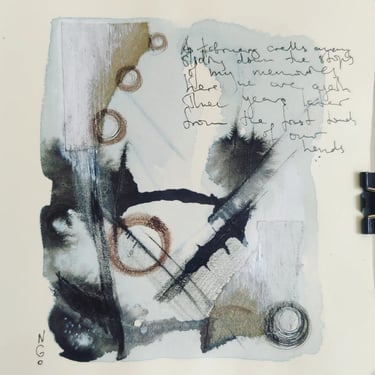

Marina created a method called Somatic Art Practice that combined our studies of embodiment with the explorations of art materials through play and experimentation. It was that kind of art I could never imagine, let alone allow myself to do — weird experiments with installation, video, writing, meditative sensorial painting. I cherished every day and found solace in those meetings during the lockdowns — we couldn’t go outside, but inside was a never-ending journey of exotic experiences.

Exploring somatic art gave me more clarity not just about BMC but also about my own process and place inside it, my health issues, and gradually transformed the relationship with my body into a more moving, mutually listening and caring one. It made sense to speak to my body-mind through art — not dance routines, or sets of yoga exercises, or therapeutic interventions. All the painful, weird, dream-like states could become art — there was no judging and no corrections.

We experimented with techniques I’d never heard of before. Witnessing the results, some part of me (that sounded suspiciously like my mother) would protest at the ‘weird squiggles’ that ‘a three-year-old could do’. I often wondered where was the area of artistic value and where was the value of the process in itself. It took me (and still takes) effort and time to let go of trying to make ‘good, beautiful, approvable’ pieces, and just follow my curiosity instead.

I would call it — making art from the body (although the brain is also part of the body). I guess the main difference I felt with my past art experiences is that before it was coming from quite an external idea of what is good, and the flow of my own inspiration had to pass through many filters of what ‘should be’ in a very mental and controlling manner. I started to feel bored by dance, theatre and visual art that only existed to look good, to show the effort of the form at any cost, that didn’t make me feel or be curious to explore.

On the other end of it, there was a personal therapeutic process where the form didn’t even matter. I felt like somatic art can be anything, coming from the physical field to interweave emotions, memories, and words in a new way. It can be meditative, therapeutic, anatomical, abstract, or performative.

In a way, it made me realise that all art is an act of creation, not just something nice to see on paper. Creation can be taken into business, kitchen, bedroom, daily relationships — anything. Embodying your own vessel for creativity is the kindling of a vital spark, making your own internal space and source of inspiration. To be inspired, I could look into myself, my subconscious, and roam those wild landscapes (like some kind of Narnia).

Somehow, my childhood joy of painting came back. It took time to allow myself to be one of those ‘three-year-old’ artists. My love for psychology and Jungian work, for tango, for touch — all could be seen emerging in some new way. The memories in my tissues, the embryonic states, the things I don’t even know the meaning of — they had space now.

And change, which was previously imposed on me, became something I could choose and something that could set me free.